Today’s blog is written by PhD student Nian Wang, who is visiting our group for 6 months from the Institute of Geology and Geophysics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS) in Beijing. Nian’s work deals with the geological evolution and chronology of several lunar meteorites. Her visit follows Xiaojia Zeng visit to Manchester a couple of years ago, who also wrote a blog on China space exploration plans. In the blog below, Nian describes the Chang’e-4 mission, which lifts off tonight aiming for the lunar farside!

Overview of the Chang’e-4 mission

The upcoming Chang’e-4 mission will be another milestone event in China’s space exploration history, since it will be the first ever controlled landing to be made on the lunar far side. And it’s coming now!

The Chang’e-4 mission, as planned, will be launched on December 8th (Beijing time) by the CZ-3B rocket from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center, located in the Sichuan province of China. Chang’e-4 will be the second soft-landing mission of the Chinese Lunar exploration Program (which comprises orbital missions, soft-landing missions, and eventually sample return missions), and was originally a back-up for Chang’e-3. Benefiting from the success of Chang’e-3, the configuration of Chang’e-4 was adjusted to meet new scientific objectives, and will open a new era of lunar exploration by landing on the lunar farside. The putative planned landing site for Chang’e-4 is in Von Kármán crater (centre area at latitude 44.8°S, longitude 175.9°E ) in the largest impact structure in the Solar System, the South-Pole Aitken basin (SPA) [1].

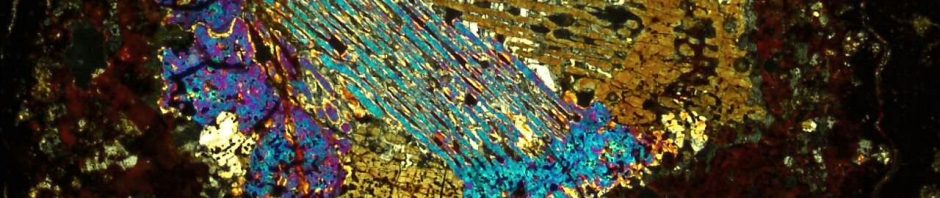

Landing site

The Von Kármán crater on the lunar farside [from Wu et al., 2017].

Scientific objectives

The Chang’e-4 mission is a lunar farside landing and roving mission that consists of a lander, a rover, and a relay satellite. The farside shields all kinds of radio waves emitted from the Earth, making it an ideal place for cosmic radio spectrum detection. In addition to observing the early Universe, Chang’e-4 will also return key information on the Moon’s geological evolution hidden away in the old and large SPA basin. Chang’e-4 contains six domestic scientific payloads made in China and three international scientific payloads. Overall, Chang’e-4 scientific activities will mainly focus on very low frequency radio astronomical observation, topographic survey in the roving area, and investigation of the mineralogical composition and shallow structure of the Von Kármán crater floor, in order to achieve the following scientific objectives [2-3]:

- Study of the deep-layer material composition of the Moon.

- Perform lunar-based astronomical observation of radio waves.

- Study the formation, evolution, topography and chemical characteristics of craters in the SPA.

- Investigate the interaction of Earth wind and solar wind with the Moon.

- Monitor impacts on the Moon.

Scientific Payloads

Relay Satellite – Queqiao

Because the lunar farside is always shielded from the Earth, neither the lander nor the rover can directly communicate with ground stations. A relay communication satellite is thus necessary to enable communication.

The line-of-sight visibility between the Earth and relay satellite around the lunar L2 Point [from Wang and Liu, 2016].

The Queqiao relay satellite [from Wu et al., 2017].

The Queqiao relay satellite carries two scientific payloads to conduct astronomical observations [1]:

- The Netherlands Chinese Low-Frequency Explorer (NCLE).

- A laser corner retro-reflector with a diameter of 17cm.

In addition, two microsatellites, the lunar microecosphere and the large-aperture laser angle reflector, named Longjiang-1 and Longjiang-2, were also launched together with Queqiao.

The lander

The lander is equipped with four scientific payloads [1]:

- A Descent Camera (DeCam).

- A Landform Camera (LaCam).

- A low-frequency radio spectrometer (LFS).

- A Neutron and Radiation Dose Detection.

Design configuration of the Chang’e-4 lander [Image: Chinanews.com].

The rover

At the time of writing this blog, the name of the Chang’e-4 rover has not been announced yet. Based on the last ten name candidates, there is a possibility that it will be named Bajie, which has so far received the most votes [5]. The Chang’e-4 rover comprises four scientific payloads [1]:

- A pair of Panoramic Cameras (PanCams).

- An infra-red imaging spectrometer (VNIS).

- A lunar ground Penetrating Radar (LPR).

- A neutral atom analyser.

Design configuration of the Chang’e-4 lunar rover [Image: Chinanews.com].

Some insights into the historic names used in the Chang’e Missions

China has a long history, and thus lots of myths and legends, from which most Chinese missions, and especially the recent space missions, have chosen their names, such as Chang’e, Queqiao, Mozi, Wukong and so on. Many of these mission names were selected by people through internet polls. Names associated with Chinese legends are always the most popular because there are meaningful and easy to understand for Chinese people. Here are some stories about the names used in the Chang’e-4 mission.

Chang’e

Chang’e, flying to the Moon [6].

Queqiao

The annual reunion of Niuliang and Zhinv on Queqiao [7].

Best wishes to Chang’e-4 and to all the space exploration missions!

References

[1] Wu W R,Wang Q,Tang Y H, et al. (2017) Design of Chang’E-4 lunar farside soft-landing mission. Journal of Deep Space Exploration 4(2), 111-117.

[2] Ye P J, Sun Z Z, Zhang H, et al. (2017) An overview of the mission and technical characteristics of Change’4 Lunar Probe. Science China Technological Sciences 60(5), 658-667.

[3] Wang Q, Liu J (2016) A Chang’e-4 mission concept and vision of future Chinese lunar exploration activities. Acta Astronautica, 2016, 127:678-683.

[4] http://finance.chinanews.com/gn/2018/08-15/8600428.shtml

[5] http://www.myzaker.com/article/5b7557b95d8b544f33268b7c/

[6] https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%AB%A6%E5%A8%A5/68389?fr=aladdin

[7] https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%B9%8A%E6%A1%A5/1309743?fr=aladdin

Pingback: Chang’e 5 mission samples reveal Moon lavas dating back less than 2 billion years – the youngest we’ve seen | Earth & Solar System