Most iron meteorites originated from the cores of asteroids that had differentiated – these are called magamtic irons. Some iron meteorites, called non-magmatic irons, come from asteroids where the differentiation process was interrupted. Iron meteorites are composed primarily of iron (obviously!), nickel, sulphur, carbon and phosphorous. They are classified according to their chemical composition and structural features.

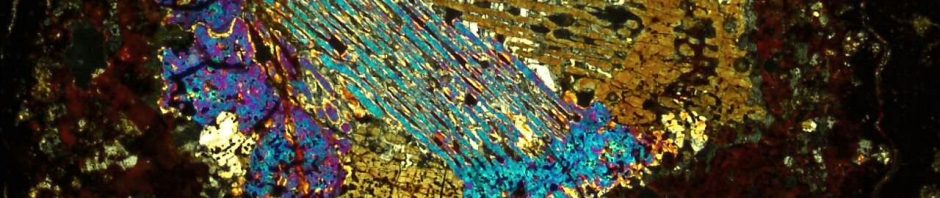

One feature seen in some iron meteorites is called the Widmanstätten pattern.

The iron and nickel in these meteorites for two minerals: kamacite and taenite. These meteorites cooled very slowly over millions of years, and as they cooled crystals of kamacite and taenite formed. This crystalline structure is known as a Widmanstätten pattern. The size of the crystals depends on how slowly they cooled – generally speaking the more slowly it cooled the larger the crystals. Their size is also affected by the nickel content. The minerals have different resistances to acid, and so the crystal structure can be exposed by etching with acid.

So we had a slight problem with our sample of the Gibeon meteorite. For reasons I won’t go into, “those marks” (aka the Widmanstätten patterns) were polished off the surface of our sample. This left a very shiny surface, but that wasn’t quite what we wanted!

On Monday afternoon we ventured out from the comfort of our Isotope Group labs, up to the unfamiliar world of the Chemistry Lab, to etch the newly polished surface and re-expose the Widmanstätten pattern. We used a 10% solution of nitric acid in methanol, which we brushed over the surface. The patterns started to appear very quickly, and were visible within a minute. After 1 minute the acid was neutralised with a weak solution of sodium hydroxide, and the sample rinsed with lots of methanol. We then repeated the process a 2nd time. After the first attempt we could see the patterns, after a 2nd attempt they were very clearly visible. We then dried the meteorite in an oven to remove the remaining methanol.

We were rather worried that we might dissolve the whole meteorite and end up with a solution of green goo! But fortunately the process appears to have been a complete success, as you can see in the picture of the freshly etched patterns at the top of this page.

Pingback: The Secret Life of Meteorites, as revealed by the Virtual Microscope | Meteorites: The Blog from the Final Frontier